Sociology professor finds Pittsburgh the ideal laboratory

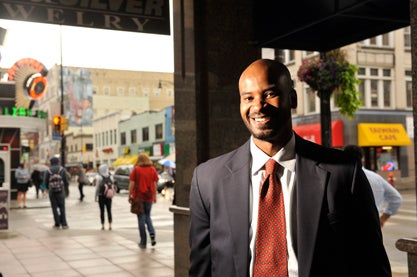

When Waverly Duck was first offered a job in the Department of Sociology at the University of Pittsburgh Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences, he jumped at the opportunity.

When Waverly Duck was first offered a job in the Department of Sociology at the University of Pittsburgh Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences, he jumped at the opportunity.

As a specialist in race and ethnicity and an urban sociologist, he was intrigued by the city’s unique demographics: Its rise and fall as a steelmaking empire; its transition to a hub of technology and medicine; and the integration of old and new world cultures that have long characterized Pittsburgh’s hilly, idiosyncratic streets.

“You could not ask for a better laboratory as a sociologist, especially an urban sociologist: 93 different neighborhoods, each one of them having a very distinct character,” says Duck, who came to the University in 2009, shortly after finishing his postdoctoral studies at Yale. “It was just too fantastic in terms of multiple ways to do research.”

The city also reminded him of his native Detroit, a setting that strongly influences his research interests.

“Detroit is just an amazing city, from its decline to now—its remaking of itself, trying to transition itself from manufacturing. I imagine it’s going to look very similar to Pittsburgh,” he says.

The son of an auto worker and a receptionist, Duck believes his working-class background shaped him for the work he would later do. Hoping to forge a career that would allow him to impact social policy and engage in academic debates, he earned his PhD at Wayne State University. Operating from gut instinct, he contacted Elijah Anderson, a renowned sociologist who was then at the University of Pennsylvania. Duck landed a job as an unpaid researcher, allowing him to study under both Anderson and another professor, Randy Collins.

One of his voluntary assignments was to collect demographic information for a death penalty case. The subject had started working as a lookout for a drug dealer at the age of 8, graduating to a corner by 12 and his own operation by 16. At 21, prosecutors were seeking the death penalty.

When Duck visited that man’s neighborhood, he was shocked to see that everything he had described was still happening much the same way it had during the dealer’s childhood.

“I decided to go back and try to tell the story of that community,” he says, offering it as a microcosm of other impoverished urban areas: “It could be Detroit, it could be Milwaukee, it could even be Pittsburgh.”

The project evolved into a book, Precarious Living: The Orderliness of African American Poverty, which is currently under contract with the University of Chicago Press. Based on five years of ethnographic data, the book examines the role drug dealing plays in the fictionalized community of Bristol Hill.

Instead of viewing the drug trade as a sign of disorder, Duck argues that the local code of conduct allows dealers to act not as outsiders, but rather as “established insiders who are well integrated into community life.”

Duck had followed Anderson to Yale when he got the call for an interview at Pitt.

“I tried to be humble when I was interviewed, but I was excited,” he says. He was already an admirer of faculty members Kathy Blee, Suzanne Staggenborg, and Akiko Hashimoto, and the opportunity to collaborate with scholars through the School of Social Work’s Center on Race and Social Problems was a significant draw.

The rest of his colleagues, and particularly the students, have exceeded his expectations.

“I think you people are absolutely amazing,” he says. “Their level of sophistication in terms of ideas, in terms of writing—these kids are extremely well-rounded.”

Since he arrived, Duck has quickly established himself in both his academic field and the community. A collaboration with demographer Anita Zuberi and research specialist Bob Gradeck at the University Center for Social and Urban Research yielded a study of the city’s economic and health disparities. And the New Pittsburgh Courier named Duck its 2012 Man of Excellence, honoring his commitment to community service.

The relevance of Duck’s research is reflected in current events shaping the political landscape, both locally and nationally. For example, he points to a movement that would require single mothers to establish their children’s paternity as a condition for receiving welfare. Drastic shifts in welfare, housing policies, education, and the criminal justice system are complicated by the everyday reality of the people these policies affect.

“My research engages in a lot of these massive shifts in terms of how we’re changing as a society, but also how people are making sense of these changes,” he says. “I really believe in this idea that a lot of academic institutions have about being an academic, being a scholar—but also being of service. Community service is extremely important.”